by Luminis Health

‘Dad? Can you hear me?’

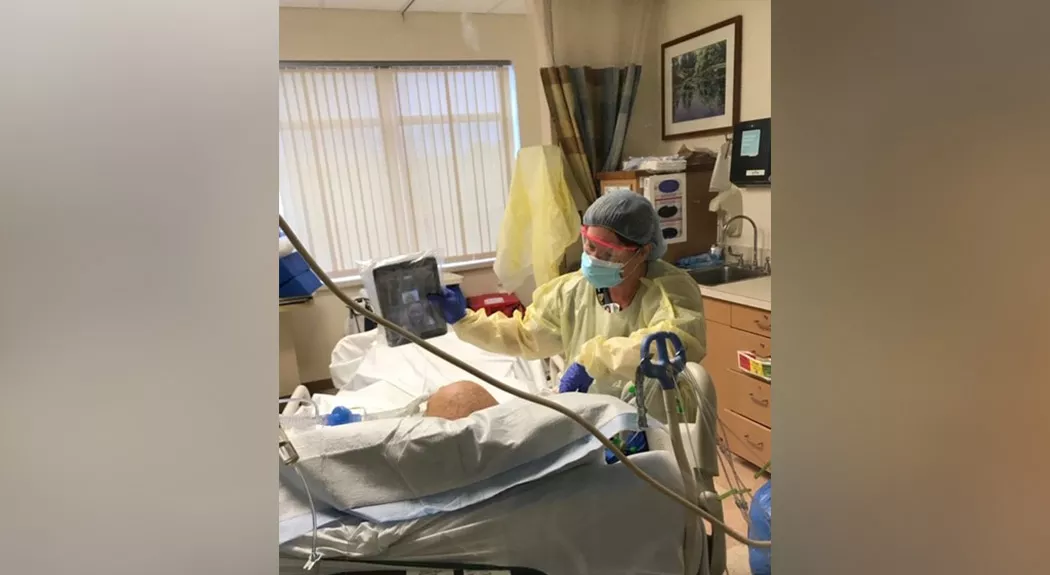

John* slowly opens his eyes at the sound of a familiar voice overriding the beeping of the medical monitor he’s been hearing next to him for the past few weeks. He is a little weak and has a sore throat. It takes him a few seconds to clear his vision and see the electronic tablet being held in front of him.

Blinking quickly, his gaze brightens the moment he recognizes the three eager faces on the screen waiting for a response. Happy tears follow quickly. And they’re not just his. Tears are flowing from him, his family, and Kelly Beraducci, the Anne Arundel Medical Center (AAMC) family coordinator holding the electronic tablet.

This is the first time John has been able to communicate with his family since being admitted to AAMC’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with severe symptoms related to coronavirus (COVID-19). The highly contagious virus led AAMC – and many hospitals across the nation – to put visitor restrictions in place for the safety of patients, families and staff.

“Having the ability to do these video calls gives patients and their families a sense of hope,” Kelly says.

“I get choked up every time I do these. It’s such a wonderful feeling of happiness to witness the moment families reconnect,” Kelly adds. “Some patients cry because they haven’t seen their families for weeks, others pray together and others laugh and joke.”

Earlier that morning, Kelly was informed by the patient’s nurse that John was going to be extubated – or taken off the ventilator. She called his family, shared the good news that John’s health was on the mend and sent them the video call details.

Throughout the day, she kept an eye on him to see when he was ready to get on camera.

“It can be a hard sight for families to see their loved ones with all the medical supplies around them,” she said. “The family had been waiting for a long time for him to get to a point where he could talk and it finally happened that day.”

Launching the Family Coordinator Program

When AAMC put visitor restrictions in place due to the pandemic, staff in Patient Advocacy and Patient Experience knew this would be a shock for patients and loved ones.

That same day, a team – formed by Inpatient Rehabilitation and Patient Relations Senior Director Kamila Frederick; Patient Experience Director Carole Groux; Patient Relations Coordinator Melissa Anderson; and Patient Advocacy, Interpretation Services and Spiritual Care Manager Anita Smith – convened to come up with a solution.

Overnight, they launched the Family Coordinator program, which created positions for redeployed employees to facilitate communication between patients, families and staff.

From left to right: Melissa Anderson, Ann Barnes, Kelly Beraducci, Janice Adams and Anita Smith.

“We realized the restrictions would provoke a lot of anxiety,” says Smith. “We wanted to make sure there was a way we could keep patients and families connected at such a crucial time, whether they were COVID-19 patients or patients in other units.”

To do this, the team redeployed a wide range of employees – including nurses, surgical advocates, patient care technicians, interventional radiology techs and more – to cover every unit. To date, there are 23 family coordinators working almost every day of the week.

Since the program launched on March 20, family coordinators have been busy reaching out to families and scheduling calls. Working with AAMC’s Information Systems department, Patient Advocacy obtained four electronic tablets for family coordinators to start scheduling video calls.

“You take for granted everything you can do by being able to pick up your phone,” Anita says. “Family coordinators and electronic tablets have become a lifeline in a time of isolation.”

Becoming a Family Coordinator

At 5 am, Kelly’s alarm goes off. She does a quick strength-training workout, showers and heads out the door to drive to the hospital, where she’s been working for the past 22 years. She goes directly to Edwards Pavilion, where she was working as a registered nurse prior to being redeployed as a family coordinator on March 25. The locker with her scrubs, shoes and PPE is still there. She changes her shoes, puts on her mask and heads over to the ICU dressed, with her supplies.

By 7 am, she’s ready for the daily nursing report.

“There are constant changes that we as family coordinators need to know about,” she says. “We’re learning more and more every day.”

By the time it’s 8 am, doctors and nurses have completed their huddle, giving Kelly a good idea of where she should go first that morning. From that moment on, the phones begin to ring.

“I get calls until my shift ends at 5:30 pm,” she says. “As nurses become available, I get updates from them to convey to the families. It’s a stressful time for everyone, so I try to be as kind, compassionate and understanding as I can be. I’m lucky to work with other compassionate family coordinators, like Sharon, who started with me. She goes above and beyond to take care of patients and their families.”

Kelly calls all the families by phone and schedules an average of eight video calls per shift according to each patient’s condition and availability. Before she sees patients, she joins the video call with their family members. Wearing an N-95 and other protective equipment, she enters the room and greets the patient.

‘Hi, I’m Kelly.’

She tries to give each family at least 10 minutes to limit her exposure, although she lets most families squeeze in a couple of extra minutes. Halfway through the call, her arms become unsteady from holding the electronic tablet for the patient. Once the call ends, it’s time to move on to the next video call with another family patiently waiting to see their loved one. Each video call is different, but one thing that is consistent from one to the next is the patient’s and family’s relief in being able to connect through a screen. Kelly, too, feels the connection. She laughs, cries, celebrates and mourns with them as if they were one of her own.

By end of her shift, Kelly’s smartwatch shows that she has walked five miles around her unit.

If she has time, she goes downstairs to the post-anesthesia care unit, where there is another family coordinator, and checks on her recovering patients.

“I went to see the very first patient I cared for as a family coordinator,” she says. “I cried during her first video call with her family and have felt very close to her since. I wanted to see her through because after so many calls with families and loved ones, you feel part of the family, too.”

At a time where there only seems to be bad news everywhere, Kelly says there’s no other feeling like seeing her patients get better and leave happy. This, she says, keeps her going.

Kelly works every other day, giving her time to slow down and relax in between her physically and mentally demanding shifts. When she gets home, she leaves her shoes outside and heads straight to the shower before greeting her family and dogs. While she changes, her husband and two teenagers prepare dinner and wait for her so they can eat together.

“There is a lot going on,” she says, adding that she went from happy outpatient surgery scenarios to situations that don’t always have a happy ending and seeing families go through a loss without being able to be next to their loved ones.

“It’s so mentally exhausting because you’re hearing the family’s anguish in their voices and trying to support them through a phone and screen. But I feel like I’m doing a great service to the families in helping them connect with their loved one.”

When she comes into the hospital, Kelly says she approaches every day with compassion and kindness, reminding herself that she, too, has a family back at home waiting to see her at the end of the day.

*Names have been changed to protect the patient’s and family’s privacy.